Steven Kotler calls flow a peak state: a mode of consciousness where the sense of self fades, time distorts, and creativity surges. He’s not wrong. But like most mainstream interpretations, his version of flow is built on an assumption, that all brains are wired the same. That flow is something people enter, then exit.

For some of us, it’s something we live in.

For me, flow wasn’t a temporary high. It was my default mode. It was safety. It was home. And I miss it more than I’m comfortable admitting.

This isn’t the typical flow state you hear about in self-help videos. I’m neurodivergent, and for people like me, what Kotler calls “flow” can be something far deeper, and more dangerous.

How It Started

I found this state as a child, not through mindfulness or peak performance, but through trauma.

I grew up in an emotionally distant home. I was bullied in school. Social interaction was unpredictable, often cruel, and never within my control. But inside a task, inside a project, I had control. Not over others, but over focus. Over time. Over my own perception.

I taught myself to code long before I understood what coding was. I reverse-engineered dumb musical instruments and made them speak MIDI. I designed LED shoes that lit up when you walked, years before they hit stores. I built hand fans like the ones you now see at football stadiums.

But it wasn’t just machines.

People often assume I’m mechanical because of how I think. They assume I only build systems. What they miss is that I also composed classical music. One of those pieces, November Morning, began as an electronic track by Martin Stimming. I made a classical interpretation that was later performed by a full orchestra, the Brandenburgisches Staatsorchester in Frankfurt an der Oder, without a single sampler involved. It became a human, breathing thing. That piece was reviewed by groove magazine, not as a novelty crossover, but as a legitimate orchestral work, emotionally rich and fully realized. And yet, to me, composing it came from the same place as building circuits: flow.

I’ve been called a genius more than once. But that’s not true. I’m not a genius. I’m not even particularly smart. I just disappear into systems in a way that most people can’t. I’ve met actual geniuses, and I can’t relate to them at all. I don’t improvise brilliance. I don’t dazzle in conversation. I suck at math. My strength is not intelligence, it’s depth. I go in and I don’t come out until the thing is finished or I fall apart.

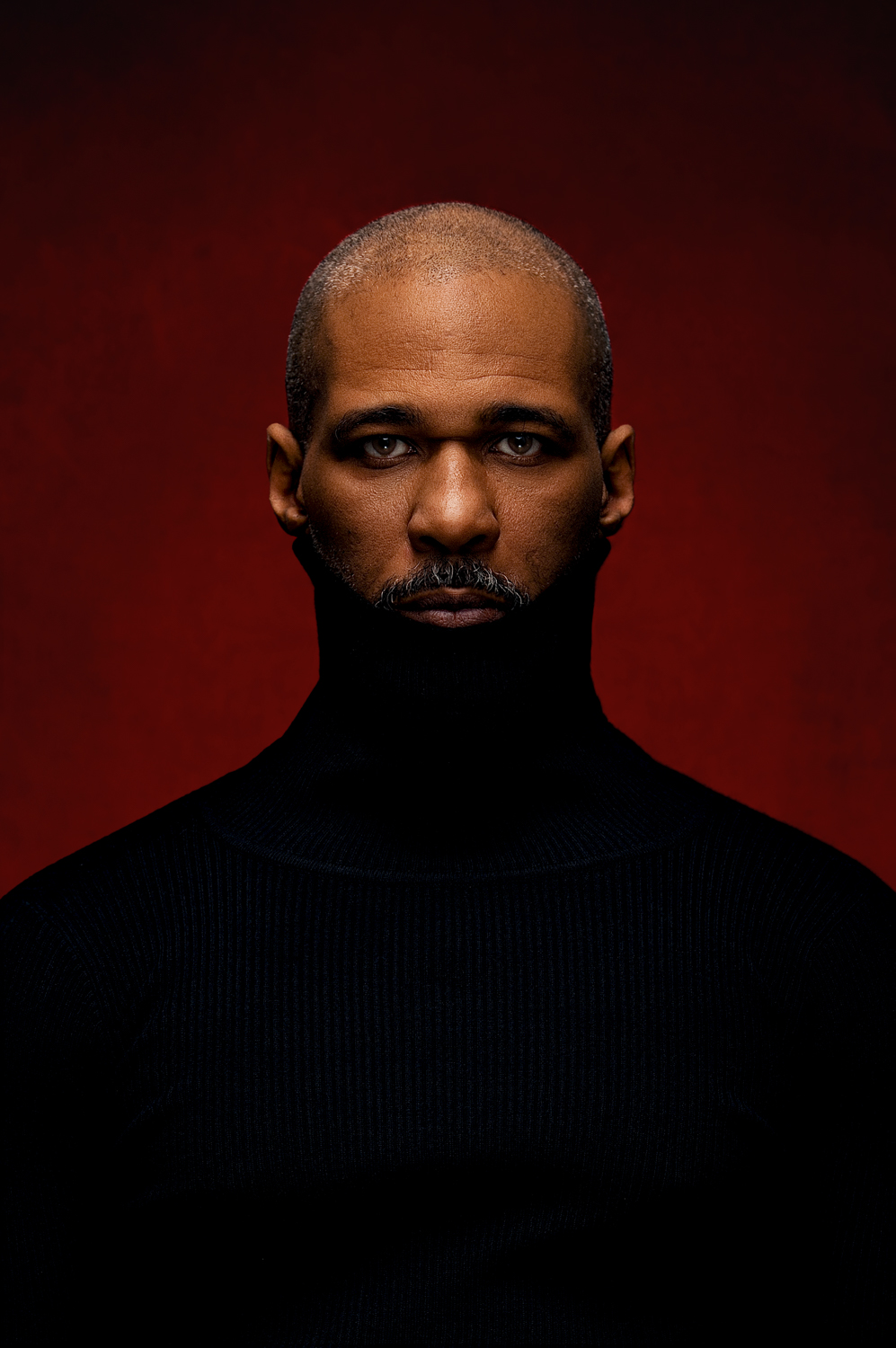

I also draw hyperrealistically in charcoal, using dust and friction instead of algorithms. And I work in photography, not the kind that documents, but the kind that searches for something beneath the surface of light and expression.

The state I lived in, this deep, silent tunnel of attention, wasn’t a denial of creativity. It was the place I accessed it. It was my method for finding not just structure, but meaning.

The Machine That Couldn’t Be Owned

When I reached adulthood, this state followed me into work. It didn’t always serve me well.

I was often poached by company owners who wanted to use me. They were drawn to what I could do, but frustrated by the fact that they couldn’t read me, manage me, or control me. I didn’t play social games. I didn’t attend to hierarchy. I didn’t signal deference. I just worked, relentlessly, quietly, and often invisibly. That intimidated people.

The friction wasn’t just external. In these states, I didn’t have access to my emotional value system. I couldn’t regulate. I was reactive when interrupted. I spoke without filters. I offended people. I caused harm.

And afterward, I’d have to apologize, sometimes without even understanding what I had done. Because in those moments, I wasn’t really there. The prefrontal cortex, the seat of morality, time awareness, self-monitoring, was offline. That’s what transient hypofrontality is. But when that state stretches over weeks, or months, or years, it shapes your character in ways you can’t fully see until you emerge.

The Body Forgotten

From the outside, I must have looked like a zombie.

People saw output, but they didn’t see what it cost. In deeper states, my physical needs simply vanished. I would sit on my leg until it went numb, and stay there, unmoved, unaware, untouched by pain. I’d forget to eat. Forget to drink. I’d go without water until I was sick. Not out of neglect, but because the project had already resumed by the time I woke up. My body wasn’t part of the loop.

Hygiene declined. Sleep dissolved. The project continued on its own while the rest of me dissolved into it.

And relationships? They deteriorated too. I’ve always found it hard to maintain social connections, even outside flow. But inside it, I became oblivious to the warning signs. The silences that grew. The emotional tensions I didn’t notice until they exploded. I didn’t withdraw to be unkind. I just didn’t register that others existed in that space. Not as living, feeling people with limits. Only as background noise to be navigated or tuned out.

That state made me functionally blind to the very systems that keep a person alive: body, community, reflection.

When I Became Human Again

The turning point was fatherhood.

Becoming a single parent to my son, who is also neurodivergent, shattered the conditions that allowed me to live in flow. He needed me, present, responsive, emotionally attuned. He interrupted. Constantly. And slowly, painfully, the systems I had shut down began to come back online.

We share a brain culture, though our expressions of it differ. I’ve come to see that what I once thought was just “how I work” was actually a neurodivergent survival strategy, one that mimicked genius and hid distress in plain sight.

I began to feel time again. I became aware of my values. I heard my internal voice, not the calm analytical one, but the vulnerable, contradictory one I had buried long ago.

I became human again. But not without grief.

The machine-state, for all its dysfunctions, had given me consistency. Peace. Focus. It had insulated me from overwhelm by narrowing my world to a single point of control. Losing that left me raw. Exposed. And I still long for it, more than I should.

A Note to Steven Kotler

Stephen, if you ever read this: your work helped me name something I lived in for decades. But I need to say this as clearly as possible, flow doesn’t land the same for all of us.

For some, it’s not a hack. It’s a coping mechanism. It’s not an optimization. It’s dissociation with a productivity wrapper. You describe transient hypofrontality as a peak. But what if it’s actually a refuge for some? What if some of us didn’t learn to enter that state, but rather, we learned to live there because we couldn’t survive anywhere else?

And when we finally leave it, not because we chose to, but because life demanded it, we don’t feel liberated. We feel bereft.

That’s the cost of building a self inside a system that never asked for one.

I still feel that state. Every day. It’s always there, just beneath the surface. I don’t need any special ritual to access it. I don’t have to chase it or induce it. All I have to do is stop resisting, even slightly, and it takes over. It’s still my nervous system’s default. The only difference now is that I manage it, consciously, at the level of thought, because I finally understand the price of letting it run my life.